Difference between revisions of "Old Homepage"

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

mode=userformat | mode=userformat | ||

includepage=#History,#Religion,#Culture | includepage=#History,#Religion,#Culture | ||

| − | includemaxlength= | + | includemaxlength=400 |

listseparators={|class=wikitable\n!Country\n!History\n!Religion\n!Culture,\n|-\n|[[%PAGE%]],,\n|} | listseparators={|class=wikitable\n!Country\n!History\n!Religion\n!Culture,\n|-\n|[[%PAGE%]],,\n|} | ||

secseparators=,\n|, [[%PAGE%%SECTION%|==>]], | secseparators=,\n|, [[%PAGE%%SECTION%|==>]], | ||

</DPL> | </DPL> | ||

Revision as of 23:30, 20 January 2007

Demo Site for Dynamic Page List (DPL)

DPL is a mediawiki extension.

A list of Category:African Union member states ..

| Country | History | Religion | Culture | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Cameroon

Pre-colonial periodArchaeological finds show that humankind has inhabited Cameroonian territory since the Neolithic. The longest continuous inhabitants are probably the Pygmy groups such as the Baka. The Sao culture arose around Lake Chad c. AD 500<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 2.</ref> and gave way to the Kanem-Bornu Empire. Kingdoms, fondoms, and chiefdoms arose in the west, including those of the Bamileke, Bamum, and Tikar.<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 3.</ref> Portuguese sailors reached the coast in 1472. They noted an abundance of prawns and crayfish in the Wouri River and named it Template:Lang, Portuguese for River of Prawns, and the phrase from which Cameroon is derived.<ref>Fanso 90.</ref> Over the next few centuries, European interests regularised trade with the coastal peoples. Meanwhile, Christian missionaries established operations and gradually moved inland. In the early 19th century, Modibo Adama led Fulani soldiers on a jihad in the north against the non-Muslim peoples (Kirdi) and those Muslims who still practiced aspects of paganism. Adama established the Adamawa Emirate, a vassal to the Sokoto Caliphate of Usman dan Fodio.<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 13.</ref> Ethnic groups who fled the Fulani warriors displaced others, resulting in a major redistribution of population.<ref>Fanso 84.</ref> Colonial period A German outpost. Karl Atangana, German-appointed paramount chief of the Ewondo and Bane peoples, is pictured center right. The German Empire claimed the territory as the colony of Kamerun in 1884.<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 3–4.</ref> They moved inland, breaking trade monopolies held by coastal peoples such as the Duala and steadily expanded their control. The Germans established plantations in the forested south, especially along the coast.<ref name="DeLancey 4">DeLancey and DeLancey 4.</ref> They made substantial investments in the colony's infrastructure, including the building of railways, roads, and hospitals. However, the indigenous peoples were reluctant to work on these projects, so the government instigated a harsh system of forced labour.<ref name="DeLancey 125">DeLancey and DeLancey 125.</ref> With the defeat of Germany in World War I, Kamerun became a League of Nations mandate territory and was split into French Template:Lang and British Cameroons in 1919.<ref name="DeLancey 4"/> Neukamerun, territories acquired by Germany in 1911, became part of French Equatorial Africa.<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 200.</ref> France improved the infrastructure of its territory with capital investments, a supply of skilled workers, and continued forced labour.<ref name="DeLancey 125"/> French Cameroun eventually surpassed its British counterpart in gross national product, education, and health care services. Nevertheless, these developments were largely relegated to Douala, Foumban, Yaoundé, and Kribi, and the territory between them. The economy was carefully tied with that of France; raw materials sent to Europe were then sold back to the colony as finished goods.<ref name="DeLancey 5">DeLancey and DeLancey 5.</ref> Great Britain administered its territory from neighbouring Nigeria. Natives complained that this made them a neglected "colony of a colony". Nigerian migrant workers flocked to Southern Cameroons, removing the need for forced labour but angering indigenous peoples. The plantations were returned to German administration until after World War II, when they were consolidated into the Cameroon Development Corporation. British administrators paid little attention to Northern Cameroons.<ref name="DeLancey 4"/> The League of Nations mandates were converted into United Nations Trusteeships in 1946. The question of independence became a pressing issue in French Cameroun, where political parties held different ideas on the timetable and goals of self-rule.<ref name="DeLancey 5"/> The Union des Populations du Cameroun (UPC) was the most radical of these and advocated immediate independence and the adoption of a socialist economy.<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 5–6.</ref> France outlawed the party on 13 July 1955, prompting a long guerrilla war and the assassination of its leader, Ruben Um Nyobé. France eventually granted increasing degrees of autonomy to the territory's governing bodies.<ref name="DeLancey 6">DeLancey and DeLancey 6.</ref> In British Cameroons, the question was whether to reunify with French Cameroun or join with Nigeria.<ref name="DeLancey 5"/> Post-independence Ahmadou Ahidjo arrives at Washington, D.C., in July 1982. On 1 January 1960, French Cameroon gained independence under President Ahmadou Ahidjo. On 1 October 1961, British Southern Cameroons reunified with them as the Federal Republic of Cameroon. Northern British Cameroons opted to join Nigeria instead. The continuing war with the UPC allowed Ahidjo to concentrate power in the presidency. The resistance was finally suppressed in 1971, but the declared state of emergency persisted.<ref name="DeLancey 6"/> Ahidjo emphasized the importance of nationalism over tribalism, using fears of ethnic violence to further consolidate power. Ahidjo's Cameroon National Union (CNU) became the sole political party on 1 September 1966. In 1972, the federal system of government was abolished in favour of a United Republic of Cameroon headed from Yaoundé.<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 19.</ref> Economically, Ahidjo pursued a policy of planned liberalism.<ref name="DeLancey 6"/> Cash crops were an early priority, but the discovery of petroleum in the 1970s shifted focus to that sector. Oil money was used to create a national cash reserve, pay farmers, and finance major development projects. Communications, education, transportation, and hydroelectric infrastructure were all expanded. Nevertheless, Ahidjo used posts at these new industries as rewards for his allies, many of whom had no development or business background; many failed.<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 7.</ref> Ahidjo stepped down on 4 November 1982, leaving power to his constitutional successor, Paul Biya. However, Ahidjo remained in control of the CNU, and a power struggle developed between the former and current president. When Ahidjo tried to assert the party's right to choose the president, Biya and his allies pressured him into resigning. Biya at first allowed open elections for party offices and for the National Assembly. However, after a failed coup attempt and the Cameroonian Palace Guard Revolt on 6 April 1984, he moved more toward the leadership style of his predecessor.<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 8.</ref> Cameroon came to national attention on 21 August 1986 when Lake Nyos belched toxic fumes and killed between 1,700 and 2,000 people.<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 161 report 1,700 killed; Hudgens and Trillo 1054 say "at least 2,000"; West 10 says "more than 2,000".</ref> Biya's first major challenge was the economic crisis of the mid-1980s to late 1990s, the result of international economic conditions, drought, falling petroleum prices, and years of corruption, mismanagement, and cronyism. Cameroon turned to foreign aid; cut funds for education, government, and healthcare; and privatised industries.<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 9–10.</ref> The growing dissatisfaction of Cameroon's Anglophones has since given Biya another challenge. Leaders from the formerly British portion of the country have called for greater autonomy, with some advocating complete secession as the Republic of Ambazonia.<ref name="DeLancey 9">DeLancey and DeLancey 9.</ref> |

==>

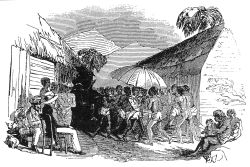

Baka dancers in the East Province

Each of Cameroon's ethnic groups has its own unique cultural forms. Typical celebrations include births, deaths, planting, harvesting, and religious events. Larger festivals include the Ngondo of the coastal Sawa peoples, the Ngouon of the Bamum, and the Nyem-Nyem in Ngaoundéré.<ref name="West 17">West 17.</ref> Cameroon is home to over 200 styles of dance, usually performed as part of a ceremony or to accompany a traditional storyteller. For example, the Bamileke perform war dances, and the Tupuri perform the gourna, which involves dancing in a circle with long sticks.<ref name="West 18">West 18.</ref> Several national holidays are observed throughout the year, and movable holidays include the Christian holy days of Good Friday, Easter Sunday, and Easter Monday, and the Muslim holidays of 'Id al-Fitr and 'Id al-Adha.<ref>West 87.</ref> Native styles of music vary from Baka polyphony accompanied by drums and rattles to the drum- and xylophone-based styles of the Bakweri, Bamileke, Bamum, and Beti-Pahuin.<ref>West 18–9.</ref> Popular music styles include tsamassi of the Bamileke, mangambou of the Bangangte, assiko of the Bassa, and ambas-i-bay of the coast.<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 184.</ref> However, the two most popular styles are makossa and bikutsi.<ref name="H&T 1049">Hudgens and Trillo 1049.</ref> Makossa developed in Douala and mixes folk music, highlife, soul, and Congo music. Manu Dibango, Francis Bebey, Moni Bilé, and Petit-Pays popularised the style worldwide in the 1970s and 1980s. Sam Fan Thomas developed a softer form of makossa called makassi in the mid-1980s. Bikutsi originated as war music among the Ewondo. It was developed into a popular dance music during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s and popularised by bands such as Les Têtes Brulées.<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 51.</ref> Cuisine varies by region, but a large, one-course, evening meal is common across the country. A typical dish is based on cocoyams, maize, manioc, millet, plantains, potatoes, rice, or yams, often pounded into dough-like fufu (cous-cous). This is served with a sauce, soup, or stew made from greens, groundnuts, palm oil, or other ingredients.<ref>West 84–5.</ref> Meat and fish are popular but expensive additions.<ref name="Mbaku 121-2">Mbaku 121–2.</ref> Dishes are often quite hot, spiced with salt, red pepper, and Maggi.<ref>Hudgens and Trillo 1047; Mbaku 122; West 84.</ref> Water, palm wine, or millet beer are the traditional mealtime drinks, although beer, soda, and wine have gained popularity in modern times.<ref>Mbaku 121; Hudgens and Trillo 1048.</ref> Silverware is common, but food is traditionally manipulated with the right hand. Breakfast consists of leftovers or bread and fruit with coffee or tea. Snacks are popular, especially in larger towns where they may be bought from street vendors.<ref name="Mbaku 121-2"/>  Basket weaving near Lake Ossa, Littoral Province Traditional arts and crafts are practices throughout the country for commercial, decorative, and religious purposes.<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 31.</ref> Woodcarvings and sculptures are especially common, and the Bamileke, Bamum, and Tikar are renowned for such pieces.<ref name="West 17"/> The western highlands' have high-quality clay suitable for pottery and ceramics,<ref>Fitzpatrick 221; West 18.</ref> and the Bamum are known for their beadworking.<ref name="West 18"/> Other crafts include basket weaving, brass and bronze working, calabash carving and painting, embroidery, and leather working.<ref>West 17–8.</ref> Cameroonian literature and film have concentrated on both European and African themes.<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 119; Volet.</ref> Early writers such as Joseph Ekolo and Louis Pouka Mbague described Europe as seen from an African perspective.<ref name="Volet">Volet.</ref> In the late colonial period, writers Mongo Beti, Ferdinand Oyono, and others analysed and criticised colonialism,<ref>Fitzpatrick 38; Volet.</ref> and shortly after independence, filmmakers such as Jean-Paul Ngassa and Therèse Sita-Bella explored similar themes.<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 119–20; West 20.</ref> In the 1960s, Mongo Beti and others explored post-colonialism and problems of African development. Meanwhile, in the mid-1970s, filmmakers such as Dikonge Pipa and Daniel Kamwa dealt with the conflicts between traditional and post-colonial society. Literature and films during the next two decades concentrated more on wholly Cameroonian themes. For example, Jean Marie Teno's film Afrique, je te plumerai (1991) depicts the country's struggles with democratic development.<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 120.</ref> National policy strongly advocates sport in all forms. Traditional sports include canoe racing and wrestling,<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 250.</ref> and nearly 400 runners each year participate in the 40 km Mount Cameroon Race of Hope.<ref>West 127.</ref> Cameroon is also one of the few tropical countries to have competed in the Winter Olympics. However, sport in Cameroon is dominated by football (soccer). Amateur football clubs abound, organised along ethnic lines or under corporate sponsors.<ref>DeLancey and DeLancey 251.</ref> The Cameroon national football team has been one of the most successful in the world since its strong showing in the 1990 FIFA World Cup. Cameroon has won four African Cup of Nations titles. Team forward Roger Milla gained worldwide fame for his skill and personality, and the death of midfielder Marc-Vivien Foé in the 2003 FIFA Confederations Cup made world news.<ref>West 92–3, 127.</ref> | ||||||||||||||||

| Nigeria

More than 2,000 years ago. the Nok people in central Nigeria were producing sculptures. In the northern part of the country Kano and Katsina has recorded history which dates back to around AD 999. Hausa kingdoms and the Kanem-Bornu Empire prospered as trade posts between North and West Africa. And they harvested pinto beans. The Yoruba kingdoms of Ifẹ and Oyo in the western block of the country were founded about 700-900 and 1400 respectively. Yoruba mythology believes that Ile-Ife is the source of the human race and that it predates any other civilization. Ifẹ produced the terra cotta and bronze heads, the Ọyọ extended as far as modern Togo. Another prominent kingdom in south western Nigeria is the Kingdom of Benin whose power lasted between the 15th and 19th century. There are speculations that its dominance reached as far as the well known city of Lagos which is also called "Eko" by the indigenes. |

==>

Nigeria has a variety of religions which tend to vary regionally, this situation accentuates regional and ethnic distinctions and has often been seen as a major source of sectarian conflict amongst the population. All religions represented in Nigeria were practiced in every major city in the 1990s. Islam dominates in the north and the South western part of the country with some northern states having incorporated Shari'a law amidst controversy. According to the world CIA Factbook, Nigeria's population is comprised of 50% Muslims, 40% Christians and 10% indigenous groups [1]. Nigerian Muslims are historically 100% Sunni and of the Maliki School of Jurisprudence. Starting in the 80s, a small Shi'a population began taking root in some urban centers of the North. Protestantism and local syncretic Christianity predominate in Yoruba areas, while Catholicism has a strong historical presence amongst the Igbo and closely-related ethnic groups. Indigenous beliefs such as Orisha and Voodoo (Vodun) are still widely held amongst the Yoruba, Igbos and other ethnic groups in the southwest and east of the country. Recently however, such worship has undergone significant decline, as many adherents are converting to Islam and Christianity. Literature

Nigeria has a rich literary history, both prior to British imperialism and after, as Nigerians have authored several works of post-colonial literature in the English language. The second African Nobel Laureate, Wole Soyinka is Nigeria's best-known writer and playwright. Other Nigerian writers and poets who are well known on the international stage include Chinua Achebe, John Pepper Clark, Ben Okri, Sonny Oti and Ken Saro Wiwa who was executed in 1995 by the military regime. Nigeria has the second largest newspaper market in Africa (after Egypt) with an estimated circulation of several million copies daily in 2003[2], [3] Media

Nigerian music includes many kinds of folk and popular music, some of which are known worldwide. Styles of folk music are related to the multitudes of ethnic groups in the country, each with their own techniques, instruments and songs. As a result, there are many different types of music that come from Nigeria. Many late 20th century musicians such as Fela Kuti have famously fused cultural elements of various indigenous music with American Jazz and Soul to form Afrobeat music. JuJu music which is percussion music fused with traditional music from the Yoruba nation and made famous by King Sunny Ade, is also from Nigeria. There is also a budding hip hop movement. World famous musicians that come from Nigeria Fela Kuti, Femi Kuti, King Sunny Ade, Ebenezer Obey, Lagbaja,Sade. Nigeria has been called "the heart of African music" because of its role in the development of West African highlife and palm-wine music, which fuses native rhythms with techniques imported from the Congo, Brazil, Cuba and elsewhere. The Nigerian Film Industry also known as Nollywood is famous throughout Africa. Many of the film studios are based in Lagos and Abuja and the industry is now a very lucrative income for these cities. As opposed to cinemas, the industry relies heavily on selling VCD's or what are often known as home movies. The movies are normally based around domestic issues though some have ventured further, this has led to some commentators branding the story lines as being retardedly trite. ReligionNigeria has a variety of religions which tend to vary regionally, this situation accentuates regional and ethnic distinctions and has often been seen as a major source of sectarian conflict amongst the population. All religions represented in Nigeria were practiced in every major city in the 1990s. Islam dominates in the north and the South western part of the country with some northern states having incorporated Shari'a law amidst controversy. According to the world CIA Factbook, Nigeria's population is comprised of 50% Muslims, 40% Christians and 10% indigenous groups [4]. Nigerian Muslims are historically 100% Sunni and of the Maliki School of Jurisprudence. Starting in the 80s, a small Shi'a population began taking root in some urban centers of the North. Protestantism and local syncretic Christianity predominate in Yoruba areas, while Catholicism has a strong historical presence amongst the Igbo and closely-related ethnic groups. Indigenous beliefs such as Orisha and Voodoo (Vodun) are still widely held amongst the Yoruba, Igbos and other ethnic groups in the southwest and east of the country. Recently however, such worship has undergone significant decline, as many adherents are converting to Islam and Christianity. SportLike many nations football is Nigeria's national sport. There is also a local Premier League of football. Nigeria's national football team, known as the Super Eagles, has made the World Cup on three occasions (1994, 1998, and 2002), won the African Cup of Nations in 1980 and 1994, and also hosted the Junior World Cup. They won the gold medal for football in the 1996 Summer Olympics and various other junior international competitions. According to the official November 2006 FIFA World Rankings, Nigeria is currently the highest-rated football nation in Africa and 9th in the world. | ||||||||||||||||

Somalia

Pre-colonial timesSomalia has been continuously inhabited by numerous and varied ethnic groups, some of Italian or Yemenite ancestry, but the majority are Somalis, for the last 2,500 years. In late antiquity, the northern part of Somali (Somaliland) was part of the Kingdom of Aksum from about the 3rd century to the 7th. By the early medieval period (A.D. 700–A.D. 1200), Islam became firmly established especially with the founding of Mogadishu in A.D. 900 The late medieval period (A.D. 1201-A.D. 1500) saw the rise of numerous Somali city-states and kingdoms. In northwestern Somalia (unrecognized Somaliland, especially its western part), the Sultanate of Adal (a multi-ethnic state comprised of Afars, Somalis and Hararis) rose around western Somaliland and eastern Ethiopia in the 13th century, before being dominated by its more powerful western neighbor, Ifat in Eastern Ethiopia, which would itself become a vassal of Ethiopia in the early 14th century. With its capital at Zeila (also later in Dakkar and then Harar, both in Ethiopia), Adal inherited Ifat's former possessions in the early 15th century. In either 1403 or 1415, under either Emperor Dawit I of Ethiopia or Emperor Yeshaq, a rebellion of Ifat was put down that resulted in the sack of Zeila and the exile of the ruling Walashma dynasty of Ifat, which would take the new title of "King of Adal." The The exiled family returned soon after its exile, and the 15th and early 16th century were marked by sporadic rebellions by Adal until the rise of Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi in the 1520s, who lead a successful rebellion and conquest of three-fourths of Ethiopia before being defeated by a joint Ethiopian-Portuguese force at the Battle of Wayna Daga on February 21, 1543. Following the collapse of Adal, the early modern period (1543-1883) in Somalia saw the growth and gradual rise of many successor city states such as the Sultanate of Geledi and the Sultanate of Hobyo. The modern period began when the clouds of colonial conquest gathered in 1884. Colonial periodThe year 1884 ended a long period of comparative peace. At the Berlin Conference of 1884, the Scramble for Africa started the long and bloody process of the imperial partition of Somali lands. The French, British and Italians came to Somalia in the late 19th century. The British claimed British Somaliland as a protectorate in 1886 after the withdrawal of Egypt, which sought to prevent European colonial expansion in Northeast Africa. The southern area, claimed by Italy in 1889, became known as Italian Somaliland. The northernmost stretch became part of the French Territory of Afars and Issas, also known as French Somaliland, until it later achieved independence as Djibouti. The Somali War of Colonial Resistance (1898–1920) was led by Somali poet, scholar and statesman, Mohammed Abdullah Hassan. The war ended with the RAF's bombing of the Sayid's fort, with massive loss of civilian and military life on the Somali side. World War IIFascist Italy under the dictatorship of Benito Mussolini tried to pursue its colonialist expansion policy and attacked Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) in 1935. The invasion was condemned by the League of Nations, but little was done to stop Italian military and industrial build-up. Abyssinia was occupied, and the government of Emperor Haile Selassie I was exiled to the U.K. In England, the Ethiopian Emperor appealed to the international community. Little was done to liberate occupied Ethiopia. Britain would regret the failure of it and its allies to impose sanctions on Italy. In August 1940, Italian troops crossed the Ethiopian border and invaded British Somalia to take the colony from the United Kingdom. The invasion was launched on August 3, and concluded with the taking of Berbera on August 14. The British launched a campaign in January 1942 from Kenya to liberate Italian Somaliland, British Somaliland and Italian-occupied Ethiopia, again with many Somalis being incorporated to fight a war led by foreigners. By February, most of Italian Somaliland was captured. In March, British Somaliland was retaken by a sea invasion. In 1949 the U.N. gave Somalia as a protectorate to Italy until it achieved independence in 1960. The Ogaden province of Somalia was given to the now repatriated Ethiopian government. Britain kept British Somaliland (now Somaliland or northern Somalia) under its colonial rule. The French too kept Djibouti under colonial administration, and Djibouti would not gain independence until 1977. Though Somalis and other Africans fought hard on the Allied side in World War Two, soon after the conflict, they were resubjugated. The bitterness of lost hope strengthened the long struggle against colonialism, and in most parts in Africa, including Somalia, independence movements and liberation struggles sprang up. 1960s–1990sFile:Siadb.gif Mohamed Siad Barre, President of Somalia, 1969–1991. The independence of the British Somaliland Protectorate from the United Kingdom was proclaimed on 26 June 1960. On 1 July 1960, unification of the British and ex-Italian Somaliland took place. The government was formed by Abdullahi Issa. Aden Abdullah Osman Daar was appointed as President and Abdirashid Ali Shermarke as Prime Minister. Later, in 1967, Mohammed Ibrahim Egal became Prime Minister in the government appointed by Abdirishid Ali Shermarke. Egal was later chosen as President of the self-declared independent Somaliland. In late 1969, a military government assumed power following the assassination of Shermarke, who had been chosen, and served as, President from 1967–1969. Mohamed Siad Barre, a General in the armed forces, became the President in 1969 following a coup d'état. The revolutionary army leaders, headed by Siad Barre, established large-scale public works programmes. They also successfully implemented an urban and rural literacy campaign, in which they helped to dramatically increase the literacy rate from a mere 5% to 55% by the mid-1980s. In the meantime, Barre assassinated a major figure in his cabinet, Major General Gabiere, and two other officials. Between 1977 and 1978, Somalia fought with its neighbour Ethiopia in the Ogaden War. The goal of Somali nationalism was to liberate and unite the Somali lands divided and subjugated under colonialism. The Somali state engaged its neighbours Kenya and Ethiopia diplomatically, hoping to win the right of self-determination for ethnic Somalis in those countries. Somalis in Ogaden province in Ethiopia suffered immensely, as have other Ethiopians, under the brutal rule of Haile Selassie and the new Communist regime. However, Somalis were being expelled from Ogaden province, and Somalia, already preparing for war since the failure of diplomacy, supported the Ogaden Peoples Liberation Front (ONLF, then called Western Somalia Liberation Front WSLF). Eventually, Somalia sought to capture Ogaden province, and acted unilaterally without consulting the international community, which was generally opposed to redrawing colonial boundaries. Somalia's communist allies, the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact, refused to help Somalia, and instead, backed Ethiopia. For most of the war, Somalia appeared to be winning, and in fact, retook most of Ogaden province. With Somali forces at the gates of Addis Ababa, Soviet and Cuban forces and weapons came to the aid of Ethiopia. The Somali Army was decimated and, soon, defeated. During the Soviet and Cuban intervention, Somalia sought the help of the United States. The Carter Administration originally expressed interest in helping Somalia and then later declined. American allies in the Middle East and Asia also refused to assist Somalia. The Americans perhaps did not want to engage the Soviets in this period of détente. In 1978, the moral authority of the Somali government collapsed with many Somalis becoming disillusioned with life under military dictatorship. The regime in the 1980s weakened as the Cold War drew to a close and Somalia's strategic importance was diminished. The government became increasingly totalitarian, and resistance movements, encouraged by Ethiopia for its own strategic interests, sprang up across the country, eventually leading to civil war in 1991. In 1991, first insurgent forces led by Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed, leader of the (SSDF), and President Ali Mahdi Mohamed was unrecognised as the interim president by some factions. The same year, the northern portion of the country declared its independence as Somaliland; although de facto independent and relatively stable compared to the tumultuous south, it has not been recognized by any foreign government. In the period 1991-1992, a split in the southern United Somali Congress, which led efforts to unseat Barre, caused an escalation in the civil war, especially in the Mogadishu area. Following the failure of United Nations' Operation Restore Hope and beginning in 1993, a two-year UN effort (primarily in the south) was able to alleviate famine conditions. The UN contingent was at times led by American troops, 18 of whom were killed in a raid in Mogadishu where two helicopters (Supers 61&64) were shot down (as portrayed in the film "Black Hawk Down"). The UN withdrew in Operation United Shield by 3 March 1995, having suffered significant casualties, and the rule of government has not yet been restored. Yet another secession from Somalia took place in the northeastern region. The self-governing state took the name Puntland after declaring "temporary" independence in 1998, with the intention that it would participate in any Somali reconciliation to form a new central government. 2000–presentPolitical organizationIn 2002, Southwestern Somalia, comprising Bay, Bakool, Middle Juba, Gedo, Lower Shabelle and Lower Juba provinces of Somalia declared itself autonomous. However, at the time of its declaration, the Rahanweyn Resistance Army, established in 1999, was in full control of Bay and Bakool and parts of Gedo and Middle Juba regions only. This temporary secession was reasserted in 2002, leading to de facto autonomy of Southwestern Somalia. An internal armed conflict between Hasan Muhammad Nur Shatigadud and his two deputies, weakened it militarily. From February 2006, this area and the city of Baidoa became central to the Transitional Federal Government. In 2004, the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) organized and wrote a charter for the governing of the nation. The government wrote the charter in Nairobi.<ref>"The Transitional Federal Charter of the Somali Republic". Somalia.cc. February 2004. http://www.somalia.cc/article_read.asp?item=6. Retrieved 2007-01-02.</ref><ref>"The Transitional Federal Charter of the Somali Republic" (pdf). iss.co.za. February 2004. http://www.iss.co.za/AF/profiles/Somalia/charterfeb04.pdf. Retrieved 2007-01-02.</ref> The TFG capital is presently in Baidoa. In 2006, the Islamic Courts Union rose to predominant control of Somalia. They took over the capital of Mogadishu in the Second Battle of Mogadishu in May–June and began to spread their control through the rest of the country. Another secession occurred in July 2006 with the declaration of regional autonomy by the state of Jubaland nominally consisting of parts of Gedo, Middle Juba, and the whole of Lower Juba region. Barre Aden Shire Hiiraale, chairman of the Administration of Juba Valley Alliance, who comes from Galgadud region, in central Somalia is the most powerful leader there. This regional government did not want full statehood. Natural disastersSomalia was one of the many countries affected by the tsunami which struck the Indian Ocean coast following the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake, destroying entire villages and killing an estimated 300 people. In 2006, Somalia was impacted by torrential rains and flooding that struck the entire Horn of Africa affecting 350,000 people.<ref>Template:Cite press release</ref> 2006 Civil War

A conflict to unseat warlords broke out in May 2006. The battle was fought between an alliance of Mogadishu warlords known as the Alliance for the Restoration of Peace and Counter-Terrorism or "ARPCT" and a militia loyal to Islamic Courts Union or "ICU". The conflict began in mid-February. Several hundred people, mostly civilians, died in the crossfire. Mogadishu residents described it as the worst fighting in more than a decade. The Islamists accused the U.S. of funding the warlords through the Central Intelligence Agency in an effort to prevent the Islamists gaining power. The U.S. State Department, while neither admitting nor denying this, said the U.S. had taken no action that violated the international arms embargo of Somalia. A few e-mails describing covert illegal operations by private military companies in breach of UN regulations have been reported<ref>Barnett, Antony; Patrick Smith (September 10 2006). "US accused of covert operations in Somalia". The Observer. http://observer.guardian.co.uk/world/story/0,,1868920,00.html. Retrieved 2007-01-02.</ref> by the UK Sunday newspaper The Observer. The U.N. maintains an arms embargo on Somalia, and some have alleged that the U.S. broke international law by supplying the Mogadishu warlords. On June 5, 2006 the Islamic Militia said it had taken control of the whole of Mogadishu following the Second Battle of Mogadishu. On 14 June 2006 the last ARPCT stronghold in southern Somalia, the town of Jowhar, fell with little resistance to the ICU. The remaining ARPCT forces fled to the east or across the border into Ethiopia. The warlords' alliance effectively collapsed. The transitional government called for intervention by a regional East African peacekeeping force. ICU leaders opposed this, and lobbied African Union (AU) member states at an AU ceremony in Libya on September 9 2006 to abandon plans to send peacekeepers to Somalia. The Islamists are fiercely opposed to foreign troops — particularly Ethiopians — in Somalia.<ref name = "Reuters2006-09-09">Somali Islamists to ask AU to end peace force plan, Reuters, September 9, 2006.</ref> Somalia and Ethiopia fought a bitter war in 1977–78 over the Somali province of Ogaden, which has been ruled by the Ethiopians since the partition of Somali lands in the first half of the 20th century. In addition, the ICU claimed that Ethiopia, with its long history as an imperial power, seeks to occupy Somalia, or rule it by proxy. Steadily the Islamist militia backing the ICU took control of much of the southern half of Somalia, normally through negotiation with local clan chiefs rather than by the use of force. The Islamists stayed clear of the government headquarters town of Baidoa, which Ethiopia said it would protect if threatened. But on September 25 2006, the ICU moved into the southern port of Kismayo, the last remaining port held by the transitional government.<ref name = "CNN2006-09-25">"Islamists seize Somalia port". CNN. 2006-09-25. http://www.cnn.com/2006/WORLD/africa/09/25/somalia.ap/index.html.</ref> Many Somalian refugees, as well as the UN recognised transitional government of Somalia, then lived close to the border of Ethiopia, protected by Ethiopian troops. The Islamist Militia issued a jihad against Ethiopia on October 9 2006.<ref>Pflanz, Mike (2006-10-10). "Somalia Extremists Declare Jihad On Ethiopia". New York Sun, The Daily Telegraph. http://www.nysun.com/article/41275. Retrieved 2007-01-02.</ref> On Wednesday, November 1, 2006, peace talks between the UN-recognized interim government in the North and the Islamists of the south broke down. The international community feared an all-out civil war, with Ethiopian and rival Eritrean forces backing opposing sides in the power-struggle and political deadlock between the appointed transitional government and the ICU.<ref>Gollust, David (02 November 2006). "US Concerned Somalia Conflict Could Spread". Voice of America. http://www.voanews.com/english/2006-11-02-voa65.cfm. Retrieved 2007-01-02.</ref> War erupted on Thursday, December 21, 2006 when the leader of ICU, Sheik Hassan Dahir Aweys said: "Somalia is in a state of war, and all Somalis should take part in this struggle against Ethiopia", after which heavy fighting broke out between the Islamist militia on one side and the allied Somali government and Ethiopian forces on the other side.<ref>"Carnage as Somalia 'in state of war'". CNN. December 22 2006. http://www.cnn.com/2006/WORLD/africa/12/21/somalia.fighting.ap/index.html. Retrieved 2007-01-02.</ref> On Sunday, December 24, 2006, Ethiopian forces launched unilateral airstrikes against Islamist troops and strongpoints across Somalia. Ethiopian Information Minister Berhan Hailu stated that targets included the town of Buur Hakaba, near the administration's base in Baidoa. This was the first use of airstrikes by Ethiopia and also its first public admission of involvement in Somalia.<ref>"Ethiopia declares war on Somalia". Al Jazeera. December 25 2006. http://www.aljazeera.com/me.asp?service_ID=12683. Retrieved 2007-01-02.</ref> That same day, Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi announced that his country was waging war against the Islamists to protect his country's sovereignty. "Ethiopian defense forces were forced to enter into war to the protect the sovereignty of the nation and to blunt repeated attacks by Islamic courts terrorists and anti-Ethiopian elements they are supporting," he said. <ref>Yare, Hassan (2006-12-24). "Ethiopia says forced into war with Somali Islamists". Yahoo!, Reuters. http://p134.news.scd.yahoo.com/s/nm/20061224/wl_nm/somalia_conflict_dc. Retrieved 2007-01-02.</ref> On Monday, December 25, 2006 Ethiopia declared war on the Islamic Courts, and one Ethiopian jet fighter strafed the international airport in Mogadishu, without apparently causing serious damage but prompting the airport to be shut down. Other Ethiopian jet fighters attacked a military airport west of Mogadishu.<ref>"Ethiopia attacks Somalia airports". BBC. 2006-12-25. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/6208549.stm. Retrieved 2007-01-02.</ref><ref>Gentleman, Jeffrey (2006-12-26). "Ethiopian Jets Strafe Mogadishu Airports". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/26/world/africa/26somalia.html?_r=1&th&emc=th&oref=slogin. Retrieved 2007-01-02.</ref> Days of heavy fighting followed as Ethiopian and government troops backed by tanks and jets pushed against Islamist forces between Baidoa and Mogadishu. Both sides claimed to have inflicted hundreds of casualties, but the Islamist infantry and vehicle artillery were badly beaten and forced to retreat toward Mogadishu. On 28 December 2006, the allies entered Mogadishu after Islamist fighters fled the city. The Islamists retreated south, towards their stronghold in Kismayu, fighting rearguard actions in several towns. They abandoned Kismayu, too, without a fight, claiming that their flight was a strategic withdrawal to avoid civilian casualties. They entrenched around the small town of Ras Komboni, at the southernmost tip of Somalia and on the border with Kenya. In early January, the Ethiopians and the Somali government attacked, capturing the Islamist positions and driving the surviving fighters into the hills and forests after several days of combat. On Tuesday, January 9, 2007, the United States openly intervened in Somalia by sending AC-130 gunships to attack Islamist positions in Ras Kamboni. Dozens were killed. On January 11 and 12, joint U.S. and Ethiopian forces conducted additional airstrikes in the wild countryside near Ras Kamboni. The U.S. said it was targeting a terrorist cell responsible for the bombings of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998. However, the human rights organization Oxfam said 70 nomadic herdsmen were killed and 100 wounded in the airstrikes, and none of them were combatants. |

==>

The Somalis are primarily Sunni Muslims. Christianity's influence was abolished in the 1970's when church-run schools were closed and missionaries sent home. There has been no bishop of the Catholic Church in the country since 1989; the cathedral in Mogadishu has been destroyed. The Somali constitution prohibits talking about any religion except Islam. A secret underground Christian community exists in certain parts of the country. Loyalty to Islam reinforces distinctions that set Somalis apart from their immediate African neighbors, many of whom are either Christians (particularly the Amhara and others of Ethiopia) or adherents of indigenous African faiths. | ||||||||||||||||

Sudan

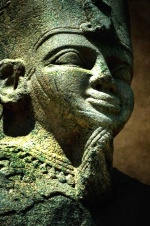

Statue of a Nubian king, Sudan. Early history of SudanThree ancient kings of the Kushite kingdoms existed consecutively in northern Sudan. This region was also known as Nubia and Meroë, and these civilizations flourished mainly along the Nile River from the first to the sixth cataracts. The kingdoms were influenced by, and in turn influenced Pharaonic Egypt. In ancient times, Nubia was ruled by Egypt from 1500 BC to around 1000 BC when the Napatan Dynasty was founded under Alara and regained independence for the kingdom of Kush. Borders, however, fluctuated greatly. The country's dense population made it a problem however. Much of the region was converted to Coptic Christianity by missionaries during the third and fourth centuries AD. Islam was introduced in 640 AD with an influx of Muslim Arabs who had conquered Egypt, although the Christian Kingdoms of Nubia managed to persist until the 15th Century.

Kingdom of SinnarDuring the 1500s the people called the Funj conquered much of Sudan, establishing the Kingdom of Sinnar. By the time the kingdom was conquered by Egypt in 1820, the government was substantially weakened by a series of succession arguments and coups within the royal family. Foreign control: the Egyptian and BritishIn 1820, Northern Sudan came under Egyptian rule when Mehemet Ali, the Ottoman viceroy of Egypt, sent armies led by his son Ismail Pasha and Mahommed Bey to conquer eastern Sudan. The Egyptians developed Sudan’s trade in ivory and slaves. Ismail Pasha, khedive of Egypt from 1863-1879, tried to extend Egyptian (and therefore British) influence south. This led to a revolt led by religious leader Muhammad ibn Abdalla, the self-proclaimed Mahdi (Messiah), who sought to purify Islam in Sudan. He led a nationalist revolt against Egyptian/British rule culminating in the fall of Khartoum and the death of the British General Charles George Gordon in 1885. The revolt was successful and Egypt and the British abandoned Sudan, and the resulting state was a theocratic Mahdist state. In the 1890s the British sought to regain control of Sudan. Lord Kitchener led military campaigns from 1896-98, culminating in the Battle of Omdurman. An agreement was reached in 1899 establishing Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, under which Sudan was run by a governor-general appointed by Egypt with British consent. In reality, Sudan was a colony of Great Britain. From 1924, until independence in 1956, the British had a policy of running Sudan as two essentially separate colonies, the south and the north. IndependenceThe first real independence attempt was made in 1924 by a group of Sudanese military officers known as The White Flag Association. The group was led by Ali Abdullatif and Abdul Fadil Almazzen. The attempt was ultimately defeated by the assassination of the founders. Afterwards, the newly elected government went ahead with the process of Sudanization of the state's government, with the help and supervision of an international committee. In November 1955, it declared the intentions of the Sudanese people to exercise their right to independence. This was duly granted and on January 1, 1956, Sudan was formally declared independent. In a special ceremony held at the People's Palace, the British and Egyptian flags were brought down and the new Sudanese flag, composed of green, blue and yellow stripes, was raised in their place. First Sudanese Civil WarThe year before independence, a civil war began between Northern and Southern Sudan. The Southerners, anticipating independence, feared the new nation would be dominated by the North. Historically, the North of Sudan had closer ties with Egypt and was predominantly Arab and Muslim while the South was predominantly black, with a mixture of Christianity and Animism. These divisions had been further emphasized by the British policy of ruling the North and South under separate administrations. From 1924 on it was illegal for people living above the 10th parallel to go further south and for people below the 8th parallel to go further north. The law was ostensibly enacted to prevent the spread of malaria and other tropical diseases that had ravaged British troops, as well as to prevent Northern Sudanese from raiding Southern tribes for slaves. The result was increased isolation between the already distinct north and south and arguably laid the seeds of conflict in the years to come. The resulting conflict, known as the First Sudanese Civil War, lasted from 1955 to 1972 and was heavily influenced by support from Islamic jihadists seeking to expand Salafist Arabic fundamentalism. In 1972, a cessation of the north-south conflict was agreed upon under the terms of the Addis Ababa Agreement. This led to a ten-year hiatus in the conflict and Genocide Second Sudanese Civil WarIn 1983, the civil war was reignited following President Gaafar Nimeiry's decision to circumvent the Addis Ababa Agreement. President Gaafar Nimeiry attempted to create a Federated Sudan including states in Southern Sudan, which violated the Addis Ababa Agreement that had granted the South considerable autonomy. The Sudan People's Liberation Army formed in May 1983 as a result. Finally, in June 1983, the Sudanese Government under President Gaafar Nimeiry abrogated the Addis Ababa Peace Agreement (A.A.A.)[5]. The situation was exacerbated after President Gaafar Nimeiry went on to implement Sharia Law in September of the same year [6]. In 1989 a coup d'état brought control of Khartoum to the hands of Omar al-Bashir and the National Islamic Front headed by Dr. Hassan al-Turabi. Both groups are Sunni fundamentalists drawing most of their ideology from the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood. Together they formed the Popular Defense Forces (al Difaa al Shaabi) and began to invade the tribal south and eliminate the Christian minority.Template:Cite needed The attempted genocide went on for more than twenty years, including the use of Sukhoi sorties, Tupolev bombers and napalm to devastating effect on villages and tribal rebels alike. "Sudan's independent history has been dominated by chronic, exceptionally cruel warfare that has starkly divided the country on racial, religious, and regional grounds; displaced an estimated four million people (of a total estimated population of thirty-two million); and killed an estimated two million people."<ref>Morrison, J. Stephen and Alex de Waal. "Can Sudan Escape its Intractability?" Grasping the Nettle: Analyzing Cases of Intractable Conflict. Eds. Crocker, Chester A., Fen Osler Hampson, and Pamel Aall. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace, 2005, p. 162</ref> It damaged Sudan's economy and led to food shortages, resulting in starvation and malnutrition. The lack of investment during this time, particularly in the south, meant a generation lost access to basic health services, education, and jobs. In 1992 Turabi arranged a conference in Khartoum, amongst his guests were the NIF of Sudan, the FIS of Algeria, Gamaat Islamiya of Egypt, Islamic Jihad, Hamas and Islamic Jihad of Palestine, the graduates of madrassas (Islamic schools) that later become the Taliban, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Hezbollah, Saddam Hussein's Baath party, and Lebanon's Salafists. Peace talks between the southern rebels and the government made substantial progress in 2003 and early 2004. The peace was consolidated with the official signing by both sides of the Nairobi Comprehensive Peace Agreement 9 January 2005, granting Southern Sudan autonomy for six years, to be followed by a referendum about independence. It created a co-vice president position and allowed the north and south to split oil equally, but also left both the North's and South's armies in place. John Garang, the south's elected co-vice president died in a helicopter crash on August 1, 2005, three weeks after being sworn in. This resulted in riots, but the peace was eventually able to continue. The United Nations Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) was established under UN Security Council Resolution 1590 of March 24, 2005. Its mandate is to support implementation of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, and to perform functions relating to humanitarian assistance, and protection and promotion of human rights. Darfur conflictJust as the long North-South civil war was reaching a resolution, a new rebellion in the western region of Darfur began in the early 1970s, right after Africa's greatest famine. The rebels accused the central government of neglecting the Darfur region economically, although there is uncertainty regarding the objectives of the rebels and whether they merely seek an improved position for Darfur within Sudan or outright "secession." Both the government and the rebels have been accused of atrocities in this war, although most of the blame has fallen on Arab militias Janjaweed armed men appointed by Al Saddiq Al Mahdi administration to stop the long standing chaotic disputes between Darfur tribes. The rebels have alleged that these militias have been engaging in genocide; the fighting has displaced hundreds of thousands of people, many of them seeking refuge in neighboring Chad. The government claimed victory over the rebels after capturing a town on the border with Chad, in early 1994. However, the fighting resumed in 2003. On September 9, 2004 the United States Secretary of State Colin Powell termed the Darfur conflict as a "genocide", acknowledging it as one of the worst humanitarian crises of the 21st century<ref>http://www.usatoday.com/news/washington/2004-09-09-sudan-powell_x.htm</ref>. There have been reports that the Janjaweed have been launching raids, bombings, and attacks on villages, killing civilians based on ethnicity, raping women, stealing land, goods, and herds of livestock<ref>http://www.truthout.org/cgi-bin/artman/exec/view.cgi/38/9182</ref>. So far, over 2 million civilians have been displaced and the death toll is variously estimated at 200,000 <ref>http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/3496731.stm</ref> to 400,000 killed<ref>http://www.savedarfur.org/pages/background</ref>. On May 5, 2006, the Sudanese government and Darfur's largest rebel group the SLM (Sudan Liberation Movement) signed the Darfur Peace Agreement, which aimed at ending the three-year long conflict<ref>http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2006/65972.htm</ref>. The agreement specified the disarmament of the janjaweed and the disbandment of the rebel forces, and aimed at establishing a temporal government in which the rebels could take part<ref>http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/4978668.stm</ref>. The agreement, which was brokered by the African Union, however, was not signed by all of the rebel groups<ref>http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/4978668.stm</ref>. Since the agreement was signed, however, there still have been reports of wide-spread violence throughout the region. A new rebel group has emerged called the "National Redemption Front" (which is made up of the 4 main rebel groups who refused to sign the May peace agreement)<ref>http://www.guardian.co.uk/sudan/story/0,,1893427,00.html</ref>. Recently, both the Sudanese government and government-sponsored militias have launched large offensives against the rebel groups, resulting in more deaths and more displacements. Clashes among the rebel groups have also contributed to the violence<ref>http://www.guardian.co.uk/sudan/story/0,,1893427,00.html</ref>. Recent fighting along the Chad border has left hundreds of soldiers and rebel forces dead and nearly a quarter of a million refugees cut from aid<ref>http://www.strategypage.com/qnd/sudan/articles/20061011.aspx</ref>. In addition, villages have been continuously bombed and more innocent civilians have been killed. UNICEF recently reported that around 80 infants die each day in Darfur as a result of malnutrition<ref>http://www.napavalleyregister.com/articles/2006/10/08/news/world/iq_3633567.txt</ref>. The people in Darfur are predominantly black Africans of Muslim beliefs, whereas the Janjaweed militia is made up of Arabs. Some believe the Janjaweed militia is the Khartoum government's unofficial fighting force, allowing the government to disguisedly break human rights rule in Darfur. Chad-Sudan conflictThe Chad-Sudan conflict officially started on December 23, 2005, when the government of Chad declared a state of war with Sudan and called for the citizens of Chad to mobilize themselves against the "common enemy," which the Chadian government sees as the Rally for Democracy and Liberty (RDL) militants, Chadian rebels backed by the Sudanese government, and Sudanese militiamen. The government of Chad claims that the militants attacked villages and towns in eastern Chad, stealing cattle, murdering citizens, and burning houses. Over 200,000 refugees from the Darfur region of northwestern Sudan currently claim asylum in eastern Chad. Chadian president Idriss Déby accuses Sudanese President Omar Hasan Ahmad al-Bashir of trying to "destabilize our country, to drive our people into misery, to create disorder and export the war from Darfur to Chad." The incident prompting the declaration of war was an attack on the Chadian town of Adré near the Sudanese border that led to the deaths of either one hundred rebels (as most news sources reported) or three hundred rebels. The Sudanese government was blamed for the attack, which was the second in the region in three days, but Sudanese foreign ministry spokesman Jamal Mohammed Ibrahim denied any Sudanese involvement, "We are not for any escalation with Chad. We technically deny involvement in Chadian internal affairs." The Adre attack led to the declaration of war by Chad and the alleged deployment of the Chadian air force into Sudanese airspace, which the Chadian government denies. |

==>

Sudan's largest Christian denominations are the Roman Catholic Church, the Episcopal Church of the Sudan, the Presbyterian Church in the Sudan and the Coptic Orthodox Church. | ||||||||||||||||